Remembering Billy and Harry.

The Zoological Society of London war memorial bears the inscription:

In memory of employees who were killed on active service in the Great War 1914-1919

Staff casualties are listed on the plaque in order of date of death. The first of these is:

29.9.1915 Henry Munro 4 Middlesex Regt ZSL Keeper

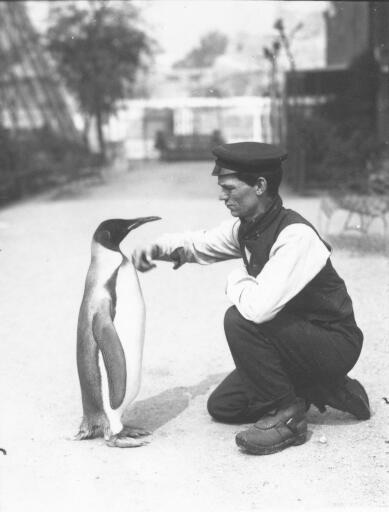

I first saw Henry pictured on a postcard from London Zoo given to me by a zoo colleague and I became intrigued by the unnamed “King Penguin with Keeper 1914”.

Harry Munro, the now named ‘Keeper with King Penguin 1914’ (as described on a recent London Zoo postcard I was given) Copyright ZSL / London Zoo/ F.W. Bond

The Photograph

Look at the photograph again. Really look at it. Look at it carefully in detail. What attracts your attention?

It would be fascinating to know how different people react to this photo – a photographer from a technical point of view or that of another zoo keeper?

On a recent Twitter #ThrowbackThursday pic.twitter.com/7Zv155kWSe @zsllondonzoo 30 January 1914 release of this picture by ZSL, there were a few brief comments including someone who misread the caption: “King Penguin with keeper Harry Munro (1914), who was sadly lost in action during WWI” to reply (hopefully tongue in cheek) that “He was a brave penguin who fought valiantly for his country” !!!

Maybe you can use the comments box at the end of the blogpost to tell me your view of this picture, I’d be interested to hear.

To me this is a fantastic photograph, considering the photographic technology of the time. It’s one of my favourite zoo archive photos.

Having myself spent around 20 years working with zoo animals, having on many occasions sitting with them and other keepers to keep the animal still enough to be photographed, I know how difficult this is today, let alone with the cameras of 1914.

I have looked at this photograph many, many times since I first started the World War Zoo Gardens research project. What do I find so fascinating about it?

It is beautifully framed, the keeper at the same height as the penguin, so somehow equal. Many photographs emphasise the height or short size of penguins measured against a keeper bending down to it. Height implies dominance or mastery. It is a species photo of a penguin, but with the photographer’s choice to include the keeper. This photo can be read as being about equality or friendliness.

The Penguin

We should not forget that in 1914 this is almost certainly a wild caught King Penguin, one of few that would have been around in European zoos at the time. These were usually brought back from Salvesen whaling or from polar expeditions, such as the famous penguin groups established at this time at Edinburgh Zoo in its first year.

In 1914, the year that this was taken, Ernest Shackleton was still on his Antarctic expedition, Captain Scott was only a year or two dead from the race to the Pole in 1912, and the extreme journey of Apsley Cherry Garrard to retrieve Emperor Penguin Eggs from the South Polar sea ice nesting grounds nearly cost him has life, recounted in his book The Worst Journey in the World.

This was a box office animal, a very topical and popular unusual bird, worthy of a photograph. A King Penguin (possibly the same one?) is pictured on another London Zoo postcard meeting royalty and Princess Mary around this date.

Getting down to penguin level holds some risks. Putting your shiny eyes near or at penguin beak height is unwise. Many press photographers have asked myself or other zoo colleagues to hold penguins or other injured seabirds at our face height to get a better cropped head shot. This is something we have to warn them against, if we value our eyes against that powerfully muscled head and neck with fish-hook of a beak.

The Keeper’s hand is blurred with movement, perhaps caught in the act of either stroking the Penguin to reassure it in this unfamiliar setting, or to keep it in place for the photograph and at a safe distance.

Is it a portrait of the Keeper as well as the Penguin? It is to me a very purposeful gaze – the Keeper’s attention is fully focussed on this bird, rather than smiling to the camera. Difficult to tell what mood the keeper is in – has he been kept too long doing this by the photographer, as sometimes happens? Is the penguin being cooperative? What mood is the penguin in? It’s also difficult to judge the keeper’s character from the photograph, but F.W. Bond as London Zoo’s photographer and staff member would have known the other staff reasonably well.

The clothes

I like the slightly naval look to the informal uniform, not the usual keeper double breasted suit and peaked cap that London Zoo staff were pictured in at the time, but a much more relaxed waistcoat, scarf, and the oddly modern looking boots. Was it a hot day the picture was taken?

I have seen these boots advertised in garden magazines of the period, very similar to the clogs worn by working gardeners and no doubt good in the wet slippery conditions a penguin or sea lion keeper would work in. They are pretty much the Edwardian / Georgian equivalent to today’s steel toe-capped keeper safety boots.

It is also resonant as a picture of a youngish man in uniform in 1914. Soon many such photographs would be taken in different circumstances, once war was declared in August. Their jobs in many workplaces, including London Zoo, would increasingly be taken by women until the war ended (see the Mary Evans picture blog below for an early WW1 female keeper).

The background

Looking into the background, unlike in many zoo photos of the time, there are no crowds of visitors around in the background. Nobody is sitting on the ornate metal bench, the path is swept clear of litter. Is this photograph taken before the zoo day begins, the end of a long day or a quiet Sunday when the zoo was mostly the preserve of ZSL fellows rather than public?

Another photograph

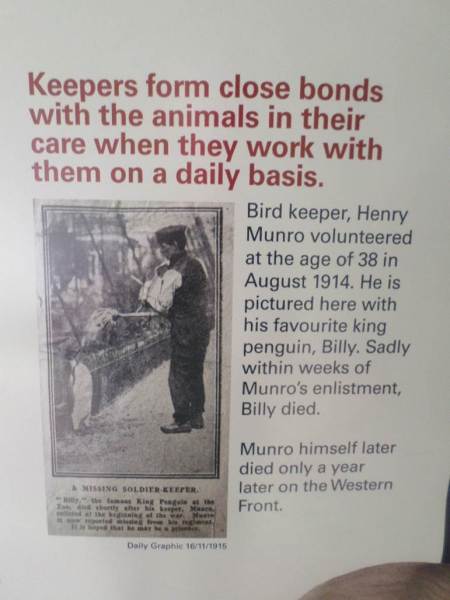

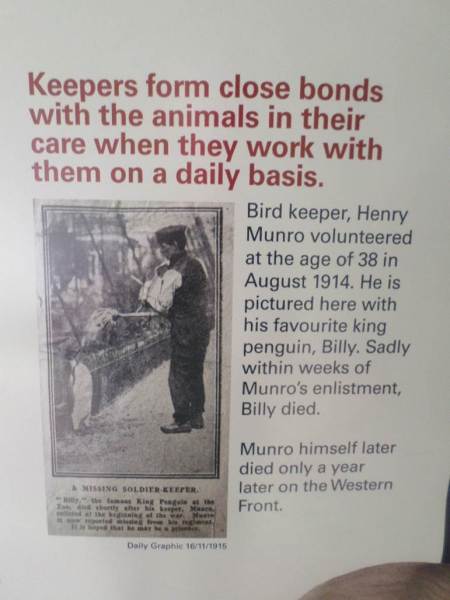

I was excited looking at London Zoo’s Zoo at War 2014 exhibition in their old elephant tunnel under the road (put together by Adrain Taylor) to see another photograph of Harry and his favourite penguin.

The Daily Graphic coverage of a “Missing Soldier-Keeper”, 16 November 1915 mentions more about this keeper – penguin relationship. It reads:

“Billy” the famous King Penguin at the Zoo died shortly after his keeper, Munro, enlisted at the beginning of the war. Munro is now reported missing from his regiment. It is hoped he may be a prisoner.

So we have a name for the King penguin as well as the keeper too.

The Keeper

But who was this ‘unnamed’ Keeper with King Penguin?

Henry Munro was the first of the London Zoo staff to be killed on active service, 29 September 1915.

On the CWGC site and UK Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914-1919 database (1921), ZSL Keeper Henry Albert or ‘Harry’ Munro is registered as born in the St. Pancras Middlesex area and enlisting in the Army in Camden Town, Middlesex (the area near Regent’s Park Zoo).

Quite old in military terms, Harry appears to have volunteered or enlisted most likely in 31 August 1914; conscription for such older men was only introduced in 1916.

Munro served as Private G/2197 with the local regiment, 4th Battalion, The Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge’s Own).

Henry (Albert) Munro served in France and Flanders from 3rd January 1915 and died aged 39 in action on or around 29th September 1915.

The Ypres Memorial (Menin Gate). Image: CWGC website

Harry has no known grave, being remembered on panel 49-51 amongst the 54,000 Commonwealth casualties of 1914 to 1917 on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial in Flanders, Belgium.

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/918293/MUNRO,%20HENRY

His death occurred a few days after September 25th 2015 saw the British first use of poison gas during the Battle of Loos after the first German use in April. The Battle of Loos took place alongside the French and Allied offensive in Artois and Champagne, following the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April to May 5th 1915 onwards).

Henry Munro served from 31 August 1914 to 5 January 1915 in Britain, and then with the 5th and then 4th Middlesex Regiment as part of the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) from the 6th January 1915 in France until his death on 29th September 1915

Much of the detail for this story comes from his Military History Sheet, and WW1 Army Service Papers (“Burnt Documents”) that fortunately have survived. Here he is listed as a “Zoological Attendant” This early service gained him the 1915 star, along with the standard Victory and British medal.

According to his service record, Henry enlisted at Camden Town on 31 August 1914. Posted as a Private, 5th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment GS (General Service) on 2 October 1914, by the 6 January 1915, Henry was posted to the 4th Battalion with whom he fought and was posted missing 29 September 1915.

Land, air and sea

I first came across the keeper’s name as ‘Harry’ Munro as it is listed in Golden Days, a 1976 book of London Zoo photographs (ZSL image C-38771X?) This same book also lists Harry as intriguingly being involved in “the army, airships and anti-submarine patrols”. Airships from coastal bases were used for anti submarine patrols because of their longer range and stamina than the flimsy aircraft of the time.

Nothing more appears on his service papers about this air and sea activity. I have little more information on this intriguing entry at present but the London Zoo typed staff lists of men of active service list him as ‘missing’ well into their 1917 Daily Occurence Book records. Many of the identifications of staff in the photographs in Golden Days were from the memory of long retired staff.

Harry Munro’s name is the first of the names of the fallen ZSL staff from the First World War, ZSL war memorial, London Zoo, 2010

Harry Munro is pictured with a King penguin but is listed on his staff record card as a keeper of sea lions. Intriguingly, several London Zoo histories list secret and unsuccessful attempts made early in the war to track submarines using trained seals or sealions. Airships were also used for U-boat spotting. I wonder if and how Harry was involved?

On the Mary Evans Picture blog “London Zoo at War” there features an interesting reprinted picture from the Mary Evans archive:

http://blog.maryevans.com/2013/04/london-zoo-at-war.html

“In March 1915, The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News featured this picture, showing a zookeeper in khaki, returning to his place of work while on leave to visit the seals, and to feed them some fish in what would be a rather charming publicity photograph.”

This soldier, according to Adrian Taylor at ZSL, working on their WW1 centenary exhibition, is George Graves, one of Munro’s keeper colleagues in khaki who survived the war and returned to work at London Zoo.

Family background

Henry Munro was born in Clerkenwell, in 1876, not far from Regent’s Park zoo (London 1891 census RG12/377) and may have worked initially as a Farrier / Smith, aged 15. His family of father William J Munro, a Southwark born Printer aged 42 and mother Eliza aged 43 (born Clerkenwell) were living in 3 Lucey Road, (Bermondsey, St James, Southwark?)

Private Henry or Harry Munro was 39 when he died, married with three children. He had married (Ada) Florence Edge on 20th November 1899. His service papers record along the top clearly written that half his pay was to be allotted to his wife.

They had three children, born or registered in Camden Town (near the zoo) by the time he was killed on active service. Hilda was 14 (born 29th March 1901), Albert Charles was 9 (born 5th June 1906, died 1989) and Elsie, 7 (born 17 August 1908, died 1977), all living at 113 Huddleston Road, Tufnell Park to the north of the zoo in London in 1915. 2 other children died in infancy according to the 1911 Census.

Interestingly, maps list Regent’s Park as having a barracks on Albany street (A4201).

Sadly Ada Florence his wife died in 1919, his later medal slips amongst his service papers being signed for by Hilda, his oldest daughter. Hilda was then around 19 in 1920 and no doubt responsible for her younger brother Albert Charles by then around 14 and of school leaving age and much younger sister Elsie, by then 12.

Staff record card information

I was lucky enough in 2014 in the ZSL Archive to look through the 1914 Daily Occurrence Book that recorded daily life and works in London Zoo, handwritten in a huge ledger each day. After many mentions thought preceding years, Munro’s name disappear from the keeper’s list in August 1914.

Even more revealing and intimate was his staff record card, an index card listing his career:

Henry Munro. Married. Born February 18 1876.

January 18 1898 Helper at 15 shillings per week.

February 21 1899 Helper at 17 shillings and 6 pence a week.

February 6 1900 Helper at 21 shillings per week.

February 6 1903 Helper at 24 shillings and 6 pence per week.

May 19 1906 Helper at 25 shillings per week.

August 15 1909 Junior Keeper on staff Antelopes at £6 per month.

December 15 1913 Senior Keeper on staff Sea Lions at £6 10 shillings per month.

Entered Army September 15th 1914.

Missing 29 September 1915.

Enlisted for war 1914, balance of pay given to wife.

Addresses listed include 177 Gloucester Road, Regent’s Park, NW (crossed out) 113 Huddlestone Road,Tufnell Park, N. (Date stamped April 23 1913)

A Helper is the lowest or youngest rank of Keeper, this phrase crops up on the ZSL London Zoo staff war memorial for young staff.

(Many thanks to Michael Palmer the archivist and library team at ZSL for their help during my visit.)

Middlesex Regimental War Diary

On 29 / 30 September 1915, the number of officers and other ranks killed, wounded and missing is listed after an account of the preceding few days of battle. Harry Munro would have been amongst these missing.

Remembering Billy and Harry, 100 years on.

Posted by Mark Norris, World War Zoo Gardens project, Newquay Zoo.

51.535288

-0.153430