“There is still a great deal of labour employed for example, in pleasure grounds and bedding out which in the present circumstances should be put to better account”

(The Garden, editorial No. 2359, 3/2/17)

Corporal Herbert Cowley returned from the trenches in 1915 to his editing desk at The Garden magazine, walking with a stick from a shrapnel wound to his knee cap. In this he was somewhat lucky as 37 of his former Kew Gardens colleagues were killed (see blog post on the Lost Gardeners of Kew WW1 ).

This was a generation of gardeners for whom ‘digging trenches’ had a deadly double meaning. Active in the Kew Guild for Old Kewite staff as its secretary, he also edited the Kew Guild Journal, recently placed online. After four years as journal editor from 1909 to 1914 and time off for military service, he became editor of The Garden in 1915/16 and carried on as a gardening writer until the late 1930s.

Unlike his fallen Kew colleagues, Herbert Cowley lived to the grand age of 82, dying in Newton Abbott in Devon in November 1967. There is a lovely description of him at Dartington as:

“that eighty-year-old gentleman with the vivid blue eyes, who retired from the world of horticultural journalism in 1936, yet who still remembered everyone and everything from those days”

recalled a researcher who had tracked him down to talk about his friendship with Gertrude Jekyll (quoted on pg. 79, Beatrix Jones (1872-1959):Fifty Years of Landscape by Diane K. McGuire)

In my collection of wartime gardening books at Newquay Zoo as part of the World War Zoo Gardens project, I have a slightly musty bound year’s copy of The Garden magazine from 1917, an edition that Cowley edited. This is one of the wartime volumes I’ve bought whilst researching the wartime history of zoos and associated botanic gardens. Leafing through its yellowing pages, it is sometimes hard to believe at first that there is a war on. Only when you begin to read between the lines or look at the adverts do you begin to pick up glimpses of the upheavals caused by war on an Empire of pioneer plant hunters, foresters, farmers and botanists called back from around the world to defend their mother country.

I will feature more in detail from this random 1917 edition in a future blog post. The Garden magazine can be read online for free at https://archive.org/details/gardenillustrate7915lond – search by year – and other sites.

Herbert Cowley as Editor at The Garden magazine was no desk gardener. As a career gardener he had risen through the ranks. His father Henry was a ‘domestic gardener’. Herbert studied at Swanley College for two years, one of the last eight men students before it became a female horticultural college around 1902. Swanley then trained many lady gardeners who dug for victory in both world wars. He worked at Lockinge Gardens in Berkshire before studying at Swanley, at some point for the royal garden at Frogmore and after Swanley for the famous nursery family of Veitch’s at Feltham. One of that same family, Major John Leonard Veitch MC (Military Cross) of the Devon Regiment would be killed on 21 May 1918, one of Cowley’s Old Kewite & Veitch’s nursery family.

Cowley joined Kew Gardens and appears always to have been a popular colleague. The Kew Guild Journal describes him in 1915/16 as having been much sought after by different departments, eventually settling in the Orchid department in 1905, probably from his experience with Orchids at one of the Veitch’s nurseries’ specialities. Veitch’s employed several famous plant hunters to collect exotic plants from around the world for the conservatories and gardens of Victorian and Edwardian Britain in one of the ‘golden ages’ of British estates, big houses and impressive gardening schemes. It was the Downton Abbey age. All this would go into decline after the war as it poignantly did at Heligan Gardens in Cornwall and many places elsewhere as a result of rising costs, loss of labour, fortunes or heirs. By the time of Herbert Cowley’s death in 1967, many of these country houses, their gardens and their gardeners would have vanished into memories and yellowing pages of his gardening magazines and Country Life in bound volumes in archives.

Cowley joined Kew Gardens and appears always to have been a popular colleague. The Kew Guild Journal describes him in 1915/16 as having been much sought after by different departments, eventually settling in the Orchid department in 1905, probably from his experience with Orchids at one of the Veitch’s nurseries’ specialities. Veitch’s employed several famous plant hunters to collect exotic plants from around the world for the conservatories and gardens of Victorian and Edwardian Britain in one of the ‘golden ages’ of British estates, big houses and impressive gardening schemes. It was the Downton Abbey age. All this would go into decline after the war as it poignantly did at Heligan Gardens in Cornwall and many places elsewhere as a result of rising costs, loss of labour, fortunes or heirs. By the time of Herbert Cowley’s death in 1967, many of these country houses, their gardens and their gardeners would have vanished into memories and yellowing pages of his gardening magazines and Country Life in bound volumes in archives.

From early on Herbert Cowley was active in learning, sharing and passing on information, a quality that any good gardening writer needs, through Kew’s Mutual Improvement Lectures in 1906/7 season. Sadly the prewar lecture lists contain the names of some of the Kew staff including C.F. Ball who would soon be killed on active service. Cowley left Kew around 1907 to join The Gardener magazine as a subeditor (later called Popular Gardening).

Herbert Cowley became Assistant Editor at a different title, The Garden in 1910. This was the magazine he was to return to as Editor in 1915/6 until 1926; this is the magazine that I have a 1917 edition in my collection. Cowley then edited Gardening Illustrated from 1923-26, another success in a long career as a gardening journalist and writer. At some point he worked for Wallace & Co of Tunbridge Wells, nursery-men and landscape architects. He wrote his final (?) book The Garden Year from Tunbridge Wells in 1936; March & April excerpts of his advice are included at the end of this blog post:

“In my capacity as editor of gardening journals I have many times been asked for a practical book containing reminders for garden work all the year round. This book is specially written to supply that want – it is in fact a modern gardening calendar in book form …

Reminders for each department – utilitarian as well as ornamental – from the kitchen garden to the orchid house – will be found in these pages.

It is hoped that this book will be given a place in the front row of the gardener’s bookshelf and that it will prove useful all the year round.

The information given is based on generally accepted practice and the season for doing things in any well-ordered garden” (Preface, The Garden Year, 1936)

“Well-ordered”, “practical”, “each department” of the garden, this is the voice of the Kew-trained gardener from the Edwardian age . Cowley writes in a clear, no-nonsense advice style about gardening. At first sight there is very little personal material, so it is hard to glimpse from his writing what he made of his wartime experiences as a temporary warrior. Like many of his generation, he got on with life after the war and probably didn’t talk or write about it much.

His army records (available on genealogy sites like ancestry.co.uk) reveal that he enlisted early in the war on 7th September 1914 as No. 2477 in the 12th County of London Regiment (the London Rangers). He very quickly embarked for France by 25 December 1914, just after the famous Christmas Truce and football matches in No Man’s Land. He may well have been a Territorial Army soldier to have enlisted and embarked so swiftly. His brother Charles Cowley (b. 1890, Wantage, Berks – d. 1973, New Zealand) served in the same regiment from 1915 and became a Sergeant, invalided out with trench foot to become a musketry instructor in devon.

In one of Herbert Cowley’s postwar letters in his National Archives British Army Service records, he complains to the Army authorities in 1920 from his residence at Curley Croft, Lightwater, near Bagshot :

“I have received so far no medals whatsover for services rendered at the Front in 1914/15. I was in the 12th London Regiment and went to Belgium with the 1st Battalion on Christmas Eve.”

He would eventually be awarded the ‘Pip, Squeak and Wilfred’ trio of medals for soldiers who served so early in the war. He was also awarded the War Badge by 1916, a useful public symbol which showed others that he had been injured and demobilised, protecting him from the comments and white feathers of the ignorant or unknowing. Cowley had got what was known as a ‘Blighty’ wound, serious enough to get him invalided out of the army but one that allowed him to live an active life. He was to suffer other family tragedies though.

Ever the gardener, he wrote for The Garden a letter on March 28 1915 about plants in France whilst overseas with the BEF, published 10 April, 1915 about a need for a “seeds for soldiers” scheme,

“The suggestion re. quick-growing seeds is excellent. Delightful instances are now to be seen of dug-outs, covered with verdant green turf, garden plots divided by red brick and clinker paths suggestive of an Italian Garden design. Some plots are now bright with Cowslips, Lesser Celandine and fresh green leaves of the Cuckoo-Pint, wild flowers obviously lifted from meadows and ditches nearby. Yet the roar of heavy guns and the roll of rifle fire is incessant. Verily the Briton is a born gardener.” The Garden, 10.04.1915

This is an area extensively covered in Kenneth Helphand’s Defiant Gardens chapter on Trench Gardens.

Alongside part of an RHS lecture from the RHS journal April 1915 by James Hudson on the “Informal and Wild Garden”, The Garden’ s Editor F.W. Harvey has printed an evocative article by Herbert Cowley on “A Garden in the War Desert” about a war damaged village and famous chateau garden at Zonnebeke near Ypres in Belgium.

“Our Sub-Editor at the Front”, Cowley is recorded in the 1916 Kew Guild Journal as being “wounded twice” in the spring battles of Ypres in 1915. He was slightly wounded in late April 1915, reported in The Garden of 8 May 1915:

” For the past eight days we have been in severe battle. I am slightly wounded by shell – only a bruised rib and am in hospital. Dreadful warfare is still raging … we must win!”

Looking through his army and pension records, he was more seriously wounded on May 4 1915, as GSW Right Knee (either Gun Shot Wound or shrapnel wound?). His medical entry is hard to read on the ‘burnt documents’ as these Blitz damaged records are known. The circumstances are reported in The Garden on 15 May 2015:

“Rifleman H. Cowley … has again been wounded in action and is now in hospital at Oxford … wounded in the knee whilst bandaging another soldier in the trenches … Rifleman H. Cowley 2477, Surgical 7, 3rd Southern General Hospital , Oxford”

Over the next few days of fighting on the Frezenberg Ridge in the Second Battle Of Ypres, it is recorded at 1914-18.invisionzone.com website entries about the 1st Battalion, that the fighting “brought about the end of the original battalion.” The battalion had also been involved in the first German poison gas attack on 22 April 1915.

Cowley was lucky to be alive, if injured; only 53 of his original battalion comrades survived unscathed after this action at Ypres, an area soon to become as sadly well known as the Somme. The Kew Guild Journal 1916 notes his absence from the 1915 Kew Guild dinner speeches as “Our Secretary Rifleman H. Cowley (cheers) in hospital at Oxford, wounded at the knee.” Obviously a popular man as the ‘cheers’ shows. In an uncanny or eerie coincidence, the 1911 census lists his sister Annie (b. 1887) as being a nurse in domestic service to the Prentice family of the oddly named Ypres House, Rye in Sussex.

By the end of the 1915, Herbert Cowley would be invalided out of the Army, be recovering from wounds and married to Elsie Mabel Hurst on 8th December 1915 in Kingston. By the end of this same year, several more of his Kewite gardening colleagues would be dead. Herbert Cowley went on to have at least one son. Many of his Kew colleagues who died in the First World War left many children fatherless.

A walk in the trench cemeteries in my early twenties past rows of teenage soldiers’ graves made me feel both prematurely old and also fortunate to have a life ahead of me. Searching through book auction websites reveals Cowley to have made good use of his extra lease of life, a life denied to so many of his generation. Cowley very quickly returned his gardening and writing talents to produce many books of practical, no-nonsense advice for the gardening enthusiast, in his own way helping the war effort in the First World War’s version of Dig for Victory.

In the 1917 journal, his own book Vegetable Growing in Wartime is reviewed. His article on this topic appears soon after, amidst many articles on vegetable allotments for the novice gardener, some written by women. Cowley’s book quickly went into a second edition as the First World War Home Front food situation in Britain appeared more and more worrying. Bad harvests and the increasing German submarine attacks on merchant shipping was causing shortages, price rises and uncertainty over future supply. Rationing was introduced in Britain in the last years of the First World War. In Germany the Allied blockade was to have even greater effects on the wartime population and eventually its fighting ability.

In the 1917 journal, his own book Vegetable Growing in Wartime is reviewed. His article on this topic appears soon after, amidst many articles on vegetable allotments for the novice gardener, some written by women. Cowley’s book quickly went into a second edition as the First World War Home Front food situation in Britain appeared more and more worrying. Bad harvests and the increasing German submarine attacks on merchant shipping was causing shortages, price rises and uncertainty over future supply. Rationing was introduced in Britain in the last years of the First World War. In Germany the Allied blockade was to have even greater effects on the wartime population and eventually its fighting ability.

Herbert Cowley continued to practical small pamphlets on Storing Vegetables and Fruit (1918), Cultivation with Movable Frames (1920) and a short book on The Modern Rock Garden (a book still available as print on demand online). His largest book The Garden Year appeared in 1936, when some sources suggest his garden journalism career came to an end.

He had not given up plants though in 1936. For a well-known gardener with a dodgy knee in his fifties, a new element to his career was beginning, away from the deadlines of editing and publishing. In Theo A. Stephen’s My Garden magazine, a 1936 volume lists Cowley as leading:

“Garden Tours – starting from London on the evening of Saturday 20th, Mr. Herbert Cowley will conduct a party to the Swiss Alps. The tour will take fifteen days,returning on Sunday July 5th to London …”

So Cowley was still energetically going abroad in his fifties, despite his shrapnel wounds. Alpine plants were to remain a passion of Herbert Cowley to the end of his life in 1968. He was an honorary life member of the British Alpine Society and his Modern Rock Garden remains in print to this day.

His Kew Guild Journal obituary in 1968 mentions other plant hunting trips to the Dolomites and a notable visit to Bulgaria as a guest of King Ferdinand in the company of Kew contemporary C.F.Ball of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin in Dublin. (Ball was killed as a Private in the Royal Dublin Fusilers on 13 September 1915 as part of the Gallipoli campaign).

Cowley wrote interesting accounts early in his editorship of the Garden in late 1915, around the time his obituary appeared for Charles Ball about their shared Bulgaria trip in the special “Rose issue” of The Garden, 23 October 1915 and in the The Garden November 6 , 1915

In a future blog post, I will look at the gardening and writing career of Theo Stephens in war and peace. Owned and edited by Stephens from 1934 to 1951, My Garden was an unusual survivor amongst small magazines throughout the paper shortages of World War 2.

Cowley had a long working relationship with Gertrude Jekyll, to whom she records her thanks in A Gardening Companion:

“and lastly to her devoted friend and colleague, Mr. Herbert Cowley, editor of The Gardening Illustrated during the period of her contribution to it, for many of the photographs which materially enhance such value as this book may possess.”

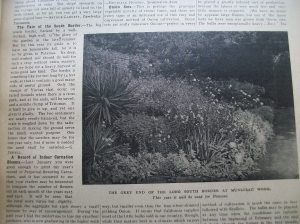

An entry in the 1917 The Garden magazine describes how Miss Jekyll dug up the South Border, one of her flower beds at Munstead to plant potatoes (photograph by Cowley?). Many of the famous postwar photographs of Jekyll’s Munstead Wood and Miss Jekyll are attributed to Cowley. Judith Tankard in a recent beautifully illustrated Country Life article launching her Gertrude Jekyll book (27 April 2011 pdf reprinted at judithtankard.com):

“in her articles published before the First World War she supplied most of the pictures herself, but after that, she relied on photographs taken by Herbert Cowley, who became Country Life‘s Gardens Editor after the departure of E.T. Cook in 1911“.

Many of Cowley’s early booklets were published by the Country Life magazine publishers / George Newnes. They produced small and useful booklets throughout the Great War well into the Second World War as part of the ‘dig for Victory’ efforts.

Cowley, according to Tankard, “was a frequent guest at Munstead Wood [and] snapped the famous picture of Jekyll strolling in her Spring Garden in 1918.” He is remembered as a prolific photographer in his Kew Guild Journal 1968 obituary by A.G.L Hellyer, a noted editor of Amateur Gardening and garden writer (1902-1993) in the Second World War period:

“throughout the 1920s he was always a prominent figure at shows – with close-cropped hair and always a large wooden camera and stand. He seemed to do all his own photography as well as being editor.”

By Spring 1918 when he had snapped these famous photographs, Cowley would have undertaken a more unpleasant task. As oldest surviving Cowley brother, he was busy of sorting out the probate or estate on 12 March 1918 of his older brother Henry William Cowley. Brother Henry had died whilst training on military service on 14 September 1917. Lance Corporal Henry W. Cowley TR9/76191 (his trainee / regimental number) 26th Reserve Training Battalion died in a comatose state of a cerebral haemorrhage at Napsbury Hospital St Albans. Cowley’s brother is buried near Heathrow airport at Heston (St. Leonard) Churchyard as the family lived in Isleworth, Middlesex.

Brother Henry’s service and pension records still contain the urgent telegrams from medical staff to his wife that Henry was dangerously ill in hospital. Among other records are a list of his surviving possessions to be returned, poignant personal items such as pipes, tobacco, whistle, cigars. A schoolteacher, Henry W. Cowley attested on 22 November 1915 and was mobilised for training on 16 July 1917, called up in the 34/35 year old age range. His wife Olive was awarded a pension of 26/3 a week for herself and her three children Henry F G Cowley (born 23/08/1906, d. 1986 Newton Abbott, Devon), Ivy Cowley (b. 6/01/1908) and Eric Jack Cowley (b. 24/2/1911, . 1984), all born at Heston, Middlesex. Later Herbert Cowley would again be listed professionally as ‘editor’ when he sorted his father Henry’s will or probate after his father died on 3 April 1930 at Easton, Portland, Dorsetshire.

Richard van Emden’s recent 2011 book The Quick and The Dead gives a much fuller account of how the burials, search for the missing and impact on the surviving families affected the now passing generation of surviving children and their own families right up to the present day. Some of the long-serving Kew staff such as C.P. Raffill, A.B. Melles and others worked in the Graves Registration Unit and for the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission; in this way Kew was involved in planning the planting of these cemeteries with suitable plants for the climate.

Herbert Cowley’s side of the family was not the only one to lose a relative. Two years earlier on the first day of Battle of the Somme, his wife Elsie Mabel (nee Hurst) lost her 30 year old brother Percy, a clerk. Rifleman 4278 Percy Haslewood (or Hazlewood) Hurst of the 1st /16th Battalion, London Regiment (Queen’s Westminster Rifles) was

killed on the 1st July 1916, during his battalion’s diversionary attack on Gommecourt. Percy left a wife Geraldine of 18 Teddington Park, Middlesex. His widowed clerk / accountant father Samuel and typist sister Elsie Mabel was left grieving for his loss. Like Herbert’s Kewite colleagues Rifleman John Divers and Corporal Herbert Martin Woolley, Percy H. Hurst is listed on the Thiepval memorial to the Missing of The Somme (Pier / face 13C). Several other Kew Gardens staff are listed in the Kew Guild magazine ‘Roll of Honour’ section as serving in Percy Hurst’s local London Regiment but thankfully survived.

The Kew Guild journal obituary ends with an unusual coda to Herbert Cowley’s gardening career. According to an (obituary?) article it quotes from the Western Guardian on November 9th 1967, Cowley left journalism to move to Withypool on Exmoor to run a riding school for 20 years throughout what must have been the wartime period 1940s up to the late 1950s. I wonder what this old soldier, who had seen the widespread call up and loss of horses, their grooms and riders in the Great War, made of Exmoor’s famous mounted Home Guard patrols in a very different

war, a war that would cause him more family grief.

Cowley and his wife made a final move to the Brixham area in the early 1960s, growing camellias, nerines and alpine plants. (His Western Guardian obituary notes him as an honorary life member of the Alpine Garden Society). This is where he was encountered at Dartington in his eightieth year, with his “vivid blue eyes” and excellent recall.

Herbert’s unexpected move to the West Country and retirement from journalism may be explained by a sad wartime event in 1940. His Kew Guild Journal 1968 obituary concludes that he is survived by his wife Elsie (b. 1893? d. 1969) and a son (name as yet undiscovered). However it seems one possible son is likely to have been killed in World War Two. RAF Sergeant Observer Robert Hurst Cowley, 580643, died aged only 22 on the 2nd September 1940. His 57 Squadron was flying Blenheim bombers on anti-shipping patrols over the North Sea from its base in Elgin in Scotland at the time before converting to Wellington bombers in November 1940. Robert is listed on the CWGC site as the son of Herbert & Elsie Mabel Cowley of East Grinstead, Sussex. Like many of his father’s Kew Gardens colleagues from the previous war, Robert Hurst Cowley has no known grave and is commemorated on panel 13 of the Runnymede Memorial to missing aircrew, one amongst 20327 names. Robert is also listed on the St. Thomas a Becket church, Framfield on the War Memorial as ‘of this parish’. Kew Gardens itself would lose several of its 1940s staff as aircrew during the Second World War (see future blog post), recorded on their war memorial.

I will end with some of Herbert Cowley’s March vegetable gardening advice from The Garden Year (1936). The advice in some areas would soon be out of fashion or obsolete as rationing and Dig For Victory took hold again in Cowley’s lifetime. No doubt his 1917 Vegetable Gardening in Wartime booklet would be found on the shelves or second hand bookstall, dusted off and referred to many times again.

We’ve just started planting some 1930s / 1940s varieties of veg that Cowley would be familiar with in the World War Zoo Gardens project allotment at Newquay Zoo, despite the rain, frost and soggy ground. Heritage varieties such as The Sutton broad bean seedlings, Early Onward peas and Ailsa Craig onions are all in, planted on the odd dry warm March day. By late summer they will be ready as fresh unsprayed food for our zoo animals, especially our monkeys.

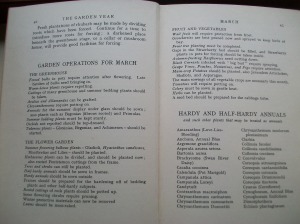

GARDEN OPERATIONS FOR MARCH (1936)

from The Garden Year 1936 by Herbert Cowley

Fruit & Vegetables

Wall fruit will require protection from frost.

Gooseberries are best pruned now and sprayed to keep birds at bay.*

Fruit tree planting must be completed.

Gaps in the Strawberry beds should be filled and Strawberry plants in pots for forcing should be taken inside.

Autumn-fruiting Raspberries need cutting down

Black Currants infected with ‘big bud’ require spraying.*

Grape Vines, Peaches, Nectarines and Figs require attention.

Main crop potatoes should be planted, also Jerusalem Artichokes, Shallots and Asparagus.

The main sowings of all vegetable crops are necessary this month.

Tomatoes will require potting on.

Tomatoes will require potting on.

Celery must be sown in gentle heat.

Herbs can be planted.

A seed bed can be sown for the cabbage tribe.

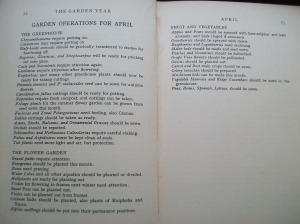

GARDEN OPERATIONS FOR APRIL (1936)

from The Garden Year 1936 by Herbert Cowley

Fruit & Vegetables

Apples and Pears should be sprayed with lime-sulphur and lead arsenate*, and bark ringed if necessary.*

Gooseberries should be sprayed with derris.*

Raspberries and Loganberries need mulching.

Melon beds should be made and seed sown.

Peaches and Nectarines should be disbudded.

Grape Vine flowers should be pollinated.

Onions should be planted out.

Carrot and Beet main crops should be sown.

Celery trenches should be prepared.

Mushroom beds can be made this month.

Vegetable Marrows and Ridge Cucumbers should be sown in the greenhouse.

Peas, Beans, Spinach, Lettuce should be sown.

* Many of these sprays are now wisely banned (2013).

Tags: botanic gardens, dig for victory garden, gardening, Gertrude Jekyll, Herbert Cowley, Kew Gardens, Kew Guild, Newquay Zoo, wartime gardening, world war 1

January 13, 2014 at 11:52 am |

[…] published in The Garden (October 16, 1915, p.514) by his friend and fellow soldier , the editor Herbert Cowley (who had been invalided out of the […]

LikeLike

July 23, 2014 at 2:34 pm |

[…] can also read more about Kew Gardens in WW1 and garden editor Herbert Cowley’s wartime career on our past blog […]

LikeLike

July 30, 2014 at 1:06 pm |

[…] can also read more about Kew Gardens in WW1 and garden editor Herbert Cowley’s wartime career on our past blog […]

LikeLike

September 2, 2015 at 8:55 am |

[…] Herbert Cowley had survived the trenches of a previous war, but lost many friends, family and colleagues. We wrote about him in a previous blogpost: https://worldwarzoogardener1939.wordpress.com/2013/03/22/dig-for-victory-1917-world-war-1-style-the-… […]

LikeLike

July 1, 2016 at 6:33 am |

[…] https://worldwarzoogardener1939.wordpress.com/2013/03/22/dig-for-victory-1917-world-war-1-style-the-… […]

LikeLike